Cyanotype is a photo printing method that has been used quite often lately. It has been on my mind for a long time to investigate the reasons why this method, which dates back to the 1840s, gained popularity again. Aslı Narin’s I for Another exhibition at Krank Gallery was a great opportunity for me to start this research. In the first part of this article, I focused on the possibilities created by cyanotype and its attractive features in its choice. In the second part, I wrote a review on Narin’s exhibition. Cyanotype is a photographic printing method created by exposure in ultraviolet light and obtained with cyan blue provided by chemicals. It is stated that one of the important

reasons for the increasing popularity of Cyanotype is its ease of application and cost- effective production (Böcekler 2019). It is an undeniable fact that the impact of cheap, unique, personalized productions brought by the DIY (Do it Yourself) culture in the emerging autonomous production and craft field has made a significant contribution to this interest. Production at Cyanotype is built on a manual labor intensive effort, which is

mostly achieved with timing, light and materials. It is possible to say that the usage areas have also diversified since it offers a technically hybrid structure and emphasizes experimentation. In fact, different sources

may accept cyanotype as photo printing, both a painting and a drawing transfer technique. The fact that it is suitable for printing with the simplest tools, for example, making a photographic print of the object without a lens, makes cyanotype advantageous. It increases the possibilities that the artist will create by moving away

from the limitation of the lens, thus liberating the production. Another important feature is that the nature of this method is unpredictable. Since the amount of chemicals used during production and the intensity of sunlight directly interfere with the resulting image, each photograph both creates a new field of experience for the producer and makes the working practice process-oriented rather than result-oriented. When the reasons I mentioned above come together, I gradually begin to realize that cyanotype differs from some principles of photography. Contrary to the classical photography technique, Cyanotype eliminates the quality of photography to freeze space and time or present them as evidence, and makes it possible to isolate the subject of photography from time and space. I think it won’t be wrong if I describe this method as a kind of installation or a collage made within the photograph itself.

Cyanotype was first used by Anna Atkins, a British botanist. Atkins recorded both the algae species and various plants that she collected and studied scientifically in a photographic book titled British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions and published this work using the cyanotype technique. Today, the operation of the cyanotype technique in an integrated manner with nature not only inspires artistic productions, but also prepares a

suitable ground for questioning the nature-human relationship again.

“If we only see what we know, how do we see what we do not know?”

Gündüz Vassaf

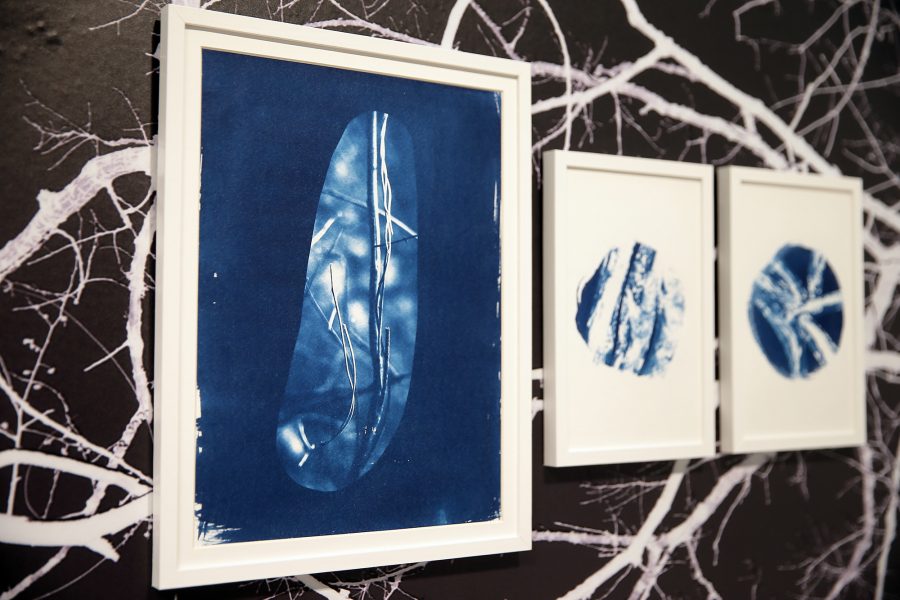

In the exhibition I for Another, Narin reminds the audience of the similarities between nature and human beings, and seeks new ways to bring these two, who have drifted apart over the years, closer together. She expresses the harmonious unity of nature with wrapped tree roots and branches. She conveys all this through cyanotype prints

that she has been working on and mastering for a long time. In the exhibition, Narin takes the viewer into a blue forest with different cyanotype images placed on a wall. When viewed from afar, the branches and roots we see in the forest resemble cell samples taken from the laboratory. When we get closer, we see that this laboratory is sections taken from various branches of a tree, namely portraits of the branches and roots. The artist opens these images for us by zooming in and out almost with a magnifying glass. The images we encounter seem to be trapped inside a drop of water, the wall of a cell, or any oval, circular, or organic form in the universe. I think this is where I got the first impression of looking at a microscope frame from that. On the other hand, the fact that everything is painted blue raises doubts that some scenes are completely organic. The images of nature that we see in the prints also bring to mind the traces that “civilization” may have left behind. The question whether a wire is wrapped around a branch or a branch is wrapped around a tree remains in quiet ambiguity in the blues of the cyanotype. Although, whether it is a piece of wire or a piece of plastic does not prevent it from making an object of nature. Because in the end, man is a part of nature, so all the tools he produces are also nature’s. What makes

these tools constructive or unpleasant is the will of man who defines himself as the most “advanced mind.” This ambiguity we encounter in the exhibition is reinforced both by the play of cyanotype with light and time, and by the tones of blue given by the cyan solution.

In the exhibition, the role of the artist as a mediator between nature and human beings, and even the fact that she explains the facts that are right in front of us and that we always skip, in all their transparency and in the simplest language possible, are very impressive. In fact, she sometimes performed this role by almost retreating between the

audience and what is seen. Narin, with a masterful move, here, by expressing the plant images in the clarity in which they are presented to her in their own normality, breaks the stereotype of transferring the photograph through the eyes of the beholder, with a single move. Such that the images we come across are almost conveyed through the

language of the subject, not through the eyes of the beholder. Although Narin’s technique involves a very different process than Atkins’ transferring a plant one-to-one, a more complex process than the traditional cyanotype method, combining the impossible-to-come-together root and branch photographs in a single photograph by creating her own frame, and combining them randomly, this nature collage created by the artist manages to present a very organic-looking photographic series. So much so that the comment made for Atkins stating “What we see is not an artist’s impression of the plant, but his own impression created by the plant” can also be made for Narin (OpenArtsArchive 2018). Moreover, this situation forces us to analyse and understand again through images of nature that are real, living, and that we often forget that they communicate with us simply because they have no language.

Signals and Exchanges 2021, cyanotype printing on watercolor paper

In the book titled Climate Change and Museum Futures, all the articles actually shout the same thing all together. While focusing on understanding the communication- relationship between human and non-human, they propose to see these two as one body rather than as separate substances. The post-Enlightenment urge to separate

culture and nature caused non-human beings to be characterized as insensitive, mindless and passive. This has also made us humans members of a system that thinks humans determine the fate of everything outside of humanity (Hall 2011). As a solution to this problem, Latour proposes the concept of “ecolozing”. That is, seeing natural and social essences as interdependent and complex and as a mutual relationship (Latour 2007).

Narin almost confirms this proposition to the audience with the video work in the exhibition. In the exhibition text it is mentioned that the way forest function is like a single body arm in arm copying or resembling the “nets on which individuals feed”. The Vulnerability of Coexistence video conveys this aspect quite clearly. The image of the

magnificent communication of two trees interlocking in a forest turns into human arms reaching, touching and wrapping each other in the continuation of the video. Tree branch with tree branch, human body with the other… But will there really be a moment when these two will meet, in other words, the tree branch and the human arm, the

human and the non-human, and we will be able to feel this sincerely? Although the name of the exhibition gives good clues about the answer to this question, unfortunately it is not that easy to say it yet.

All these integrative thoughts are nice, but it seems like we always have to be convinced somewhere far away from reality and beyond our imaginations… This exhibition made me pick up a book I read years ago again. The main character in Edwin Abbot’s Flatland, the square of the 2-dimensional world constantly imagines the 3- dimensional world, and it is forbidden by other polygons to imagine it in the system he lives in. Is it that hard to be a cube? Just like in this book, Narin pushes us to imagine new dimensions beyond the two-dimensional world we encounter in the exhibition. And in fact, through the branches of the trees, she whispers in our ears a miracle that it is

not impossible to imagine, in other words, togetherness and the desire to be one. On the other hand, while we are surrounded by many teachings and thought mechanisms such as yoga, meditation, which are intended to persuade us and suggest that we feel a part of the whole, it is difficult to think that listening, watching and

observing nature is enough. Because, on the other hand, the necessity of self- identification imposed on each of us individualizes us and puts us in a race that separates us from nature. We are all part of a whole in the world, and we are all portrayed completely differently. Just like the zoomed-in portraits of tree branches that

wrap arm in arm, presented by Narin. In the face of those who propose to be one, in the shadow of the problem of self- identification, it is only a matter of time to be separated instead of feeling like a whole. I don’t know if the issue has come this far for Narin, but when she proposes to re- evaluate this feeling, the question is quite pertinent; really, who am I to someone else?

T. Melis Golar

May, 2021

Works Cited

Böcekler, B. (2019). The Historical Development of Cyanotype from the Beginning to the

Present and an Exemplary Project: “Istanbul Blue”. Art-Art Magazine, (13), 53-86.

Hall, M. (2011). Beyond the human: Extending ecological anarchism. Environmental

politics, 20(3), 374-390.

Latour, B. (2007). To modernize or to ecologize? That is the question. Technoscience: The

Politics of Interventions, 249-72.

OpenArtsArchive. (2018, May 21). Anna Atkins Cyanotype [Video]. Youtube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pH3onQbfzc4

Vassaf, G. (1992). Praise of Hell (Vol. 25). İletişim Publishing House.

Bibliography

Abbott, E. A., & Nemli, H. F. (1999). Flatland: a story of dimensions. Ayrac Publishing House.

Alberro. H. (2019, September, 17). Humanity and nature are not separate – we must see them

as one to fix the climate crisis. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/humanity-and-

nature-are-not-separate-we-must-see-them-as-one-to-fix-the-climate-crisis-122110

Cameron, F., & Neilson, B. (Eds.). (2014). Climate change and museum futures. Routledge.

Garascia, A. (2019). “Impressions of Plants Themselves”: Materializing Eco-Archival Practices

with Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae. Victorian Literature and Culture, 47(2), 267-

303.

James. C. (2014). The Cyanotype Process. Christopher James. https://www.christopherjames-

studio.com/materials/The%20Book%20of%20Alt%20Photo%20Processes/SAMPLE%20CHAPT

ERS/CyanotypeProcessSm.pdf

Üstün, T. (2019). Blue is My Character. Fotoatlas, 27, 62-65

Exhibition credit: Aslı Narin, I for Another, Krank Gallery, Istanbul, 2021.

Fotoğraf kredisi: –

For more information;

http://www.krankartgallery.com/portfolio/bir-baskasi-icin-ben/

This article published at Unlimited in August 2021 issue.