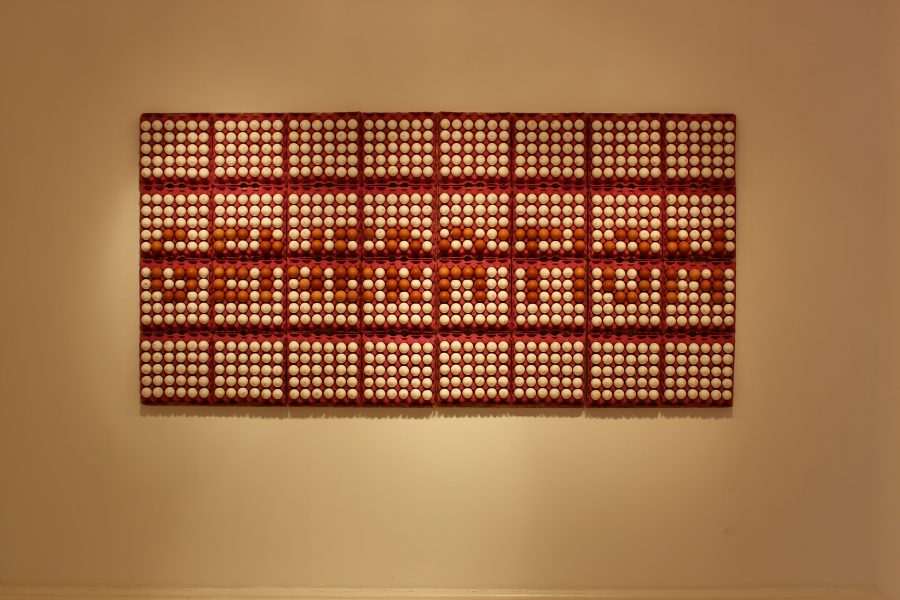

Fırat Engin meets the audience through his interdisciplinary methods by underlining the issues of consumption society, globalization, market and politics of the culture and criticism of the socio-political order. Engin conveys the current traumas, injustices, manipulative discourses, oppressions and the human behaviors and psychologies that arise as a result, through the collection of individual stories in the exhibition ‘How Long Can We Carry This Load?’.

Parallel to his past exhibition at which the artist was focused on the refugee concept, the artist refers this time to the tender contemporary problems in his exhibition by touching upon the concept of immigration, identity, memory, belonging, nation, family, home. These concepts, which have become universal problems, are interpreted through individual stories and traces instead of pluralist approaches such as nation, society and mass criticism. The artist who uses substantial materials and content vividly at his artistic production, welcomes his audience once again with this exhibition with a multifaceted dialect. He demonstrates his competence of transforming ready or found objects into a new material.

In the midst of the changing world dynamics he emphasizes that individuals ought to develop new awareness on the concepts of nation, race, gender, family while he suggests to find new ways to solve these current problems.

MELİS GOLAR : Can you mention the scope of ‘How Long Can We Carry This Load?’ exhibition? How did you form the ideology behind it?

FIRAT ENGİN : Opened last year (2016) my exhibition ‘Boats Filled with Soul, Water and Dreams!’ was on the concept of “refugees” which have especially emerged right after the Syrian civil war. The field work I carried out on this subject has led me to a radical change in my method of production in terms of content and form. As understood from this example, I always believe that an artist should destroy and rebuild himself. Since 2007 this approach has become a lifestyle for me. In this sense, every exhibition is mounted up one another and becomes a new channel, a new adventure both technically and contextually.

I think that the exhibition ‘How Long Can We Carry This Load?’ includes both all of the past accumulations and involves a brand new suggestion. The major notions such as migration, property, memory, ownership, nation, family, are manifestations of my internal feud. Up until now I prefer to be involved in the themes of my works slightly distanced with an objective perspective but this time through this exhibition, I hold the works into a more singular and subjective area.

M.G.: What kind of awareness do you want the audience to develop about the concepts you are touching upon within this exhibition? How does your advice to escape from this burden appear in the exhibition?

F.E.: Honestly, I can not tell you that I found a definite formula to redeem from this burden. However we are entering a new era in which the dogmatic and imposed definitions, the dictated concepts, fall apart, and the awareness increases against the oppressions. I think that this era was embraced in Turkey with ‘Gezi Park Protests’. I believe that our personal awareness has expanded where our awareness towards the concepts of nation, race, gender, belief, etc. has passed to a brand new phase. In this sense, I think we should move away from our ancient personal and institutional responsibilities so that we would be more capable of managing our will and allow ourselves to broach the freedom in our minds. The ‘load’ under the title of this exhibition is actually a metaphor. In this sense the concepts of memory, recollection, migration, identity, ownership, nation, family ect. must be transferred from a macro reality into a micro realm so that we could redefine these concepts in our own individuality instead of social interpretations. The communication in between the audience and the works could improve this type of awareness.

M.G.: After having an exhibition ‘Boats Filled with Soul, Water and Dreams!’ in the context of refugees, do you this time draw a parallel through this exhibition by suggesting a new / utopian land in the model of the Seeland?

F.E.: To me Sealand is a utopia of hope. We (as artists) transfer from the given subjective world to a different reality through the art making and the viewer does that through communicating with it. Sometimes this transferred reality can actually get more real, so much so that the truth can leave a more striking, more impressive and lasting effect than itself. For instance, Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ tells us the brutality of war so powerful that we have shivers even mentioning it, so much that we may feel the tragedy of the war in our veins. Sealand can be taken as an art piece. Perhaps by a coincidence, or due to the compelling circumstances, Roy Bates unveils the delusion in his mind and founds the Sealand. At the moment, there are over 200,000 passported citizens, although Sealand has no legal validity and is completely ‘de facto’. In other words, this utopic existence of a country that has no place in reality, suggests a new possibility that we would want to believe. I think that this suggestion has given us the opportunity to be free from our ancient personal and institutional responsibilities that I have just mentioned, to manage our will and to broaden the freedom in our minds.

M.G.: In 2014, CI editions you transformed a simple hamburger box from dailylife into a fetish object by painting it in chrome colors. It was referring to the consumer goods produced as artworks in editions which appeared to be the striking point of this work. Similar colors can be seen in ‘Breath’ , the window series…

F.E.: As you have mentioned, the fetishization of an object from everyday life, the provocation of the consuming reflex, was among the targets of this work. Thus, a simple, single-use object belonging to everyday life, which is produced in many editions, has revealed an idea of high commodification value towards the audience. I used chrome colors in this piece parallel to this aim. In the series of ‘Breath’ I think that the waste windows suit well the memory and recollection themes, however apart from those, it also includes concepts such as individuality, family, life and existence. Besides these, there are some overlapping sides of this object with the American crime psychologist Phillip Zambordo’s ‘Broken Glass Theory’. According to this theory; when a broken glass is not repaired, it resurrects the feeling of abandonment so that it causes destruction in other glasses, or objects around it. The study carries all these notions within this object (the waste window) as the chrome painted broken areas seeks to integrate visitors into the work by reflecting them while repositioning them in itself which has been left in desolation. So that, it gives a new ‘Breath’ to the object and to the memory.

Right: ‘Breath Series II’, 2017, found slum window, metal, chrome paint, varnish

M.G.: You produced a work criticizing and questioning the art market in terms of its relationship between the value, artwork-market and the politics of pricing through a manifesto with the piece called Art-Money / Money-Art, exhibited in the Art Beat Art Fair in 2011. As an artist whose works are owned by significant collectors and who made such an art work; how would you evaluate Turkey’s socio-political status and the position in the art market?

F.E.: Since the early 2000’s, Turkey has been changing both socio-politically and artistically. I believe that Turkey has socio-politically a vision and axial problem. It is very certain that these highly eccentric axes and political fluctuations are dragging such a geography that has deep powerful cultural and historical roots, into socio-political ambiguity. One of the most affected sectors under these uncertainties is; the art market. It is impossible to obstruct, to shut it down or to restrain art in its production area; however it is possible to affect the arts market, disrupt the mood and make many people unemployed.

In this line of thought, the art market needs to protect itself from these uncertainties. I think that this protection could be possible by avoiding everyday speculative mediatic tendencies. I think in Turkey both the viewers and the collectors have good intentions. On the other hand, I also see that we could not express well enough its intellectual extent. In this sense, current art institutions, art historians and artists have a great responsibility. Nevertheless, despite all socio-political negativities, the arts market still has a strong potential. We must institutionalize this potential by establishing new strong networks on an international scale. We no longer need to be introverted, we need outward-facing moves.

M.G.: You have reinforced your criticism by exhibiting this work particularly at an art fair. You opened ‘Boats Filled with Soul, Water and Dreams!’ exhibition in a noninstitutional space. Apart from its 3 dimensional constraints, your works appear to be integrated into the institutional stance of the space when speaking of the notion of space is very significant to the sculpture. Can you elaborate your views further on this discipline?

F.E.: From architecture to photography, from sculpture to performance, from video to installation; space is a very important dynamic for artists from any discipline. In every period of art history, we can see that space is always an area of showdown for the artists. In fact, the search for placelessness in art shows us that space is an important factor determining the content directly. I do use the different features of the space in my work. These features sometimes manifest themselves over a specific work while having a direct relation of the sculpture within space, other times, as you have mentioned in your examples, they may create a semantic stratum with the socio-cultural-political features of the space regarding an exhibition or an art piece in itself. With this latter feature, beyond its introverted and passive effect of the space on the project, it shows that it undertakes a very active and completing dynamic role on the art piece. For example at the 49th Venice Biennial held in 2001, Maurizio Cattelan installed a Hollywood caption on the highest peak of Palermo, a mafia town in the south of Italy, where 22% is unemployed. This ironic and humorous installation location (Palermo) might be regarded as a dynamic completing the work with all its socio-cultural and political features, and forging its final content in a city sinking in crime, and economically in turmoil, contrary to Los Angeles’ reputation of fame, money and popularity.

M.G: Are there any developments both in our country or from around the world, that you feel as controversial as negative or one that you find as an improvement, as positive, in terms of art politics? Why do you think that these situations transpiring in these days? Where does Turkey stand in terms of your example?

F.E.: I think we are in a new era where post-production is the dominant aspect. I can see this reality from the works such as Ai Wei Wei, Takashi Murakami, Damien Hirst and others

in Art Basel’s ‘Art Unlimited’ selection organized every year. In 2015, when I went to Art Basel I had the opportunity to see in the ‘Art Unlimited’ section, huge works produced, costing perhaps millions of dollars, many of which by big name artists in the art world.On the same date, not in the scope of the fair but again in Basel, I saw another work of Ilya Kabakov from 1998. This work is a woman’s glove, casted in bronze and painted in red (original color). The glove was placed in an area randomly on the street, as if it fell. When you try to bend it or to sweep away with a broom, you realize you can not move it and you realize that the glove is actually a piece of art. Then you can find 9 texts in 4 different languages that are placed there, and you can read the stories about the lost glove in each text. The power and poignancy of this humble installation was what I was most impressed with in Basel. We can not underestimate the fact that huge productions, shock effects, scandals will always exist in the art world. Sometimes this may even be necessary. However I believe that art is not just a matter of production, as the art field as whole must not surrender these tendencies. Because these trends are inevitably pulling the art to the daily, mediatic and popular zone. I think this zone is a dangerous and controversial one.

For more information; https://galerisiyahbeyaz.com/tr/gecmis/galeri-siyah-beyaz/2017-2018/bu-yuku-daha-ne-kadar-tasiyabiliriz