Merve Ertufan occupies gaps in the mind and turns questionable sides of the self into new topics of inquiry by manifesting riddles, paradoxes and repetitions. She “mesmerizes” the viewers, so to speak, by pulling them into

an invisible spiral with a physical twist and by urging them into a loop with dilemmas and repetitions within the exhibition space. She seeps into the depths of our minds through random questions, language twists, semi-real

stories and brain teaser riddles. I have conducted a delightful interview with Merve Ertufan on her solo show Waiting on a Scratch that brings together several installations, videos and text-based works from her few latest years.

TOMRİS MELİS GOLAR: How would you briefly describe Waiting on a Scratch?

MERVE ERTUFAN: Waiting on a Scratch is an exhibition that is made out of 6 works that I worked on 2016-2020. It is an exhibition that unfortunately demands the physical presence and engagement of the viewer with its 3 video

installations, a spatial installation, an interactive work and a book. (I say unfortunately, because the exhibition coincided with the second wave and the curfews.)

In the exhibition I try to slow down the experience of time, and offer a space for acts of rest, reflection and evaluation. I investigate the processes, formations and discrepancies that are often concealed behind language,

expressions and repeated actions of our day-to-day experiences, moving through inquiries on selfhood, cognition and consciousness.

T.M.G.: Does the pandemic have an impact on the process of this exhibition?

M.E.: Currently, we are in the midst of trying to translate the experience of the exhibition onto the digital space due to the pandemic. However, since the works were not conceived to be experienced through a personal computer screen, the works become unwatchable when repeated without alterations. For example, the work titled Can an answer be surprising? which is able to run for 22 minutes at a calm pace in its installed space, has to be sped u

about 75-80% for the flat experience of the screen. The viewer’s psychological and bodily experience behind a computer is distinctly different than the one in the exhibition space.

With this exhibition, my intention was to remove life from its fast, focused, and unceasing flow; to create a space and distance that sets up a possibility for deceleration, deviation and reflection. I think the pandemic -without our

intention to do so- is forcing us to slow down, and confront certain topics that we have been avoiding. It makes for a powerful confrontation with the fundamentals of being human, alive and existing on this earth; things we usually keep out of sight and out of mind. In this way, even if the exhibition content hadn’t changed much from April to November, it is clear that the context we are in -hence the context of the works as well- has changed quite

drastically. I hope that the audience will encounter a companion of sorts with these works, one that contemplates on similar issues.

T.M.G.: In the exhibition there are works where you treat the profoundness of language, mind and subconscious. Though it is possible to trace such elements in your previous works, still the distinctness in your methods and

your language compels the attention. How do you see this change?

M.E.: I think instead of the subconscious, the exhibition deals with the conscious and unconscious duality. Rather than psychoanalysis, the works delve into topics of language, mind and consciousness through the lens of

cognition and neuroscience. I guess I used to be more influenced by psychology in my previous works; those days I felt a need to support my works with documentary/evidential backing. For example, in works like Compliments or Sketch, I followed an artistic process of formulating rules for an environment, entering it and

observing how the said environment formed our actions that were belatedly made visible through the video camera. In these works there was a prevailing effort to gain distance on myself and/or the medium, an attempt to gaze from

outside. Somewhat experimental, a curiosity as to what kind of psychology would take over if we were to place this and that limitations on the subjects, a process that would later be edited and presented to the viewer.

However at the core of these works, there lies a belief -nevertheless doubtful- in the existence of what we call the ‘self’. In this regard, I think I was conducting a search for a true ‘self’ that would withstand all these trials in

different environments. Instead, today I employ knowledge retained from cognitive and neurological perspectives, and completely accept ‘self’ to be a speculation. This has helped me shed the need to provide documentary and/or evidential backing. A change for which I recognize Home Workspace Program of Ashkal Alwan in Beirut as being the major catalyst. I no longer search for a ‘self’; instead, Iaccept fictive narratives, and focus on medium oriented encounters mostly through text.

T.M.G.: The article of the exhibition written by L. İpek Ulusoy Akgül mentions your drawing parallels to Thomas Metzinger’s ‘Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self’. Can we hear these parallels from you too?

M.E.: That is an extremely interesting and deeply challenging book actually. It is one of the two sources for the split I was just mentioning (the other is “Nihil Unbound” by Ray Brassier, especially the first three chapters).

Philosopher T. Metzinger, in his quest to investigate his personal out-of-body experiences/phenomena during sleep from his youth, goes on to answer questions of what it means to be human, how do we experience ourselves, and

what are these things that we call will, self, perception, etc. At the core of the work lies the fact that we are not able to see how we think, which is to say we don’t know how we operate, we don’t know how an idea comes or goes, how we perceive an object, or how we perceive a subject. At this point, where we are not able to open up our skulls and see how the neurons fire, this philosophy book talks about what kind of myths/legends take over to fill that void. It is a substantial work that takes part in the current whole post-human, inhuman, nonhuman, human and artificial intelligence discourse; and, -unlike Metzinger’s “Being No One”- this book is intended for a wider audience with a less technical language.

Although, I’m not sure if it can be called drawing a parallel. I think these two books informed the workings of all the projects in the exhibition.

T.M.G.: Although you said that you are freed from the feeling of grounding the themes on proofs and records, I still think that you have a tendency of keeping strong references. Apart from Metzinger are there any other

references that influenced you and this exhibition?

M.E.: You’re so right. The works in the exhibition contain elements of what we may call anecdotal and autobiographical fictions, told in the form of first person singular. However, I don’t feel like it’s my place to present these as just my thoughts, because at the end of the day these topics have been treated for thousands of years in many different religions and languages. So, I don’t try to form a sense of ‘I’; instead, I consult the expertise of people that have researched these topics for years in order to understand what these auto- fictional elements entail within the scope of the exhibition. The exhibition has many sources. Some specific works were influenced by

more smaller and specific parts of different references; but as major influences that impacted several works at the same time, I can count these: Ego-Tunnel, T. Metzinger; Nihil Unbound, Ray Brassier; Insurmountable Simplicities, Thirty-nine Philosophical Conundrums, Roberto Casati & Achille Varzi; The Infinite Image, Zainab Bahrani; Crow With No Mouth, Ikkyú; Forthcoming, Jalal Toufic. Apart from these there are many others that seep into separate works, but I believe that list would be very long and detailed. Maybe we can mention them if they come up during the chat on specific works.

T.M.G.: The video installation called Orbit encapsulates the viewer into a spiral both visually and bodily while accompanying the hypnotizing effect that is spread throughout the exhibition as a whole. As the work becomes

site-specific the above mentioned harmony delicately addresses the features of the physical exhibition space. At this point I wonder about your sequence of production.

M.E.: The installation titled Orbit, imagines a video projection that circles a column, the viewer around the video and sphinx prints on the surrounding walls. In the exhibition space (Depo), the columns are the dominant architectural feature, and exhibitions are often developed with regard to these. After the exhibition was confirmed, I visited this unique space and realized I wanted to do a site inspired work; and decided to make a work that puts a column in the center, rather than having all these columns exist in between works. That’s why in this project, what I had imagined as a cone in the beginning ended up becoming a semi-pseudosphere (somewhat like a trumpet’s bell); the shape came before everything else. I went many ways before making up my mind on what to put on this shape. For a while, I thought I’d put an animation of a cheetah running, another time I thought of making a video inspired by the zoetrope. The content got sorted once I realized I wanted to put the sphinx on the walls to encircle the whole

project.

Sphinxes are mythological characters that guard the threshold, often placed at the main gates of cities to monitor and control who enters and leaves the city. In this work, the Alacahöyük Sphinxes are there due to their transient

and ambiguous nature. They are partly made of woman, lion, eagle, and snake, but never can they become a whole woman, lion, eagle or a snake. They exist neither inside, nor outside, neither part of the architecture, nor free standing. They assisted me in thinking through hybridity and indefinability. In the exhibition, the spaces between two sphinxes repeat as white and black. It became a project through which I was able to think about the absolute and the ambivalent.

T.M.G.: Why do these sphinxes stand there, can you reveal it a little bit more?

M.E.: Sphinx has been accompanying me since the beginning actually. The exhibition’s starting point was language games and riddles; and one of the famous riddles takes place between the Sphinx and Oedipus. I got hooked

from there, and sphinx is a very interesting character that seems to keep giving. Their double-ness opens up to infinity, their guarding of transitions and thresholds provide a strange concept of limit. Apart from these, things that

Reza Negarestani and Z. Bahrani write about Lamassus seem adaptable to sphinxes to a certain extent. For example, Negarestani takes them as war machines, Bahrani writes about their transient existence and image power.

However, the riddle I just mentioned is the real reason that sphinx is the most prominent image within the exhibition. The riddle has many versions, one of them goes like this: -Which creature walks on four feet in the morning, two feet at noon, and three feet in the evening? In the story, the riddle was one which no one had answered correctly. But Oedipus answers right by saying “man”. And the Sphinx catches fire and dies. While researching this riddle, I came across a text titled, “Oedipus’ body & the riddle of the Sphinx”, published in 2006 at the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism by Rob Baum, an academician who deals with performance, drama and body. In her text, Baum mentions how Oedipus lived with a disability all his life, due to his feet being bound as an infant and getting abandoned after the prophecy. In addition, she talks about how the story was a legend long before it was a tragedy, and that one version of the legend takes place pre-language. In all probability, Oedipus is able to solve the riddle because of his disabled feet, and in this version where he can’t speak words, he answers the riddle by

pointing at himself. I think this is why I turned the lines in the video in the counter direction of the

rest, and placed the sphinxes at a height of the legs and knees of the visitors, possibly causing them to slightly lose balance/stability.

T.M.G.: I must admit you played with my equilibrium!

In the work called Copycat’s Strife with the Original you are bringing up the subject of authenticity and disparity between the copycat and the original. Furthermore the notion of time plays an important role between these two.

At this point, where does inspiration stand for you? Is it possible to talk about an absolute originality?

M.E.: An absolute original is difficult, it may be easier to think of an absolute copycat. At least, we may be able to get close to an answer to the question “is it possible?”. Although, an absolute copycat won’t confirm the existence of an absolute original. God seems to be the absolute original in monotheistic traditions, I’m not sure about the polytheistic ones. Outside of the religious discourse, it seems we have yet to figure out the sources of our thoughts,

actions and even material compositions. I guess when we talk about absolutes, the quest becomes too big. So big that we can’t distance ourselves enough to see the topic at hand in its totality.

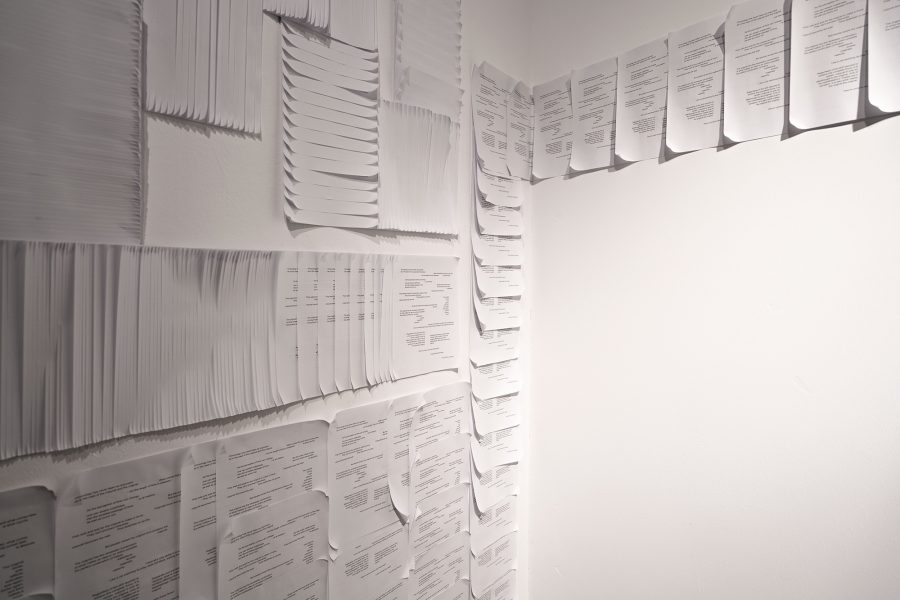

In specificity of the work; Copycat’s strife with the original is a text-work printed on a4 papers, in which an “Off-duty Copycat” compares him/herself with the original. In the exhibition we have 720 copies placed on top of each

other resembling a snake or a labyrinth. Each page has some section covered by the one above, and only in the one at the uttermost top can the viewer read the full text, which is also the one that came out of the printer first. In the text, the Copycat character seems to be obsessed with chronology; too aware of the fact that even if s/he were to watch with pure focus and repeat the Original’s actions as fast as possible, s/he can never actually be

simultaneous with, nor precede the Original. The Original is free from the Copycat, proceeding with independent thoughts; whereas the Copycat is bound by the Original. I think this is why s/he tries to build self-worth through

this text, which is written when s/he is actually off-duty. Since it’s not easy being a Copycat, can a complete imitation have a value on its own?

T.M.G.: I believe there are so many details to touch upon within the work An echo too late. You are collating the tale of Khazar Princess and Narcissus with your own stories. While you tell the stories from others one can not

hear any echo, however once you begin to tell your own story one can hear the belated echo of your voice. How did you set up this play of the self?

M.E.: An echo too late is actually the work I worked on the longest in the exhibition. It started out as a sound work in 2016, which later extended to a much longer length and then shrank back to a 14 minutes video. The project starts from a moment in which the narrator fails to recognize herself. In this phenomenon/illness, termed as facial agnosia, one loses the ability to recognize faces. Although in the story of the video, this only lasts for a few seconds, it prompts the narrator to describe her facial features, draw up a personal history, and share with the viewer her thoughts on the mechanisms of our processes of formulating a self. Narcissus and Princess Ateh accompany the story, which is told in the singular first person tense, even though the voices are edited with echos from different sources. The appearance of these two characters are in fact related to the phenomenon of time in cognitive process. The conception of an acting “self” and an observing “selfhood” forms the basis of this project. Needless to

say, the observer follows behind, and tries to make sense of the actions of the “self” in a speculative manner. However there is a lag in between. The video argues that this lag exists within a very delicate balance and can easily be disrupted. Here, Narcissus and Ateh are presented as cases in which this temporal difference between the action and the perception, (or in the case of this work) the real and the image becomes extreme. Narcissus is a widely used reference, however I approached this story through the idea that the lake in question is enchanted. Because of the spell, Narcissus’ image exists in sync with real time, thus Narcissus is confined in an atemporal parenthesis between his gaze and the image’s gaze. So, he can’t remove his gaze, he turns into an absolute “self”, thereby transforming into a passive character with no agency. He slowly vanishes in front of his image.

Ateh is at the other end of the spectrum (Dictionary of the Khazars, Milorad Pavić). She is given two mirrors, on one of them the image appears after real time, on the other it appears prior to real time. Her eyelids were inscribed

with letters to protect her from the enemies during her sleep; letters that are deadly for those who read it. The spell makes itself visible to her through these two mirrors, and ends up killing the princess. Because; while one of the

mirrors shows the previous blink, the other one shows the latter. Ateh reads the letters between two blinks, and dies. As you mentioned, in the video, stories of Narcissus and Ateh are narrated through a single sound from a central source, whereas the stories created and told by the narrator are heard through echoes, reflections and parallels. I made this particular choice, because I think that we can think more clearly and accurately while evaluating an abstract alternative or a phenomenon that is considered to be external. But actually, this is a project in which I try to go beyond reductive and detrimental binaries such as inside and outside, self and other, and reach towards a more global scale in relation to these questions.

T.M.G.: To me one of the most significant reasons for being impressed by this exhibition was; that it does not hold any concern of delivering a direct opinion about socio-political current world problems. The notion of art

works having to relate to or touch upon social or political situations has, in my eyes, become annoyingly persistent. In my opinion it is quite striking to discover such a self-oriented story as in Waiting on a Scratch that at the

same time puts forth many existential topics tangling once in a while in our minds.

M.E.: I think the most important aspect of contemporary art -even the term is coined after the “contemporary”- is that it deals with the issues of the present day. But I feel like we sometimes define the issues of the day in a limited

manner. When we define today -the time period we’re addressing- in a narrow way, we find ourselves confined in a restricted present. Almost like Narcissus’ gaze. Confined within its own parenthesis, stuck, like a flickering

light beam. My intention was in fact to expand this parenthesis, to disrupt the gaze and enable other perspectives to manifest themselves. I don’t think it is necessary to address urgent issues of the day in order to engage with the sociopolitical realm. An artwork can be political through revealing the unknown, presenting utopias or reaching the masses; as well as through its aesthetic means; such as approach and methodology. In Waiting on a Scratch, I worked on our perceptions of concepts such as the self, the body, ownership and agency that are constantly transforming along with technology- and perhaps they will go through many cycles of

transformation in the future. I guess through this exhibition, I was able to present the means I use while trying to disentangle these existential questions -those that help me- for the viewer. I think the methodology I took on enables encounters, makes space for empathy and intends to slow things down overall.

————————————————

- Lamassu is a Assyrian protective deity of thresholds. It has a human head, the body of

a bull or a lion, and bird wings. Their main differences from the sphinx is that they

often have male human heads and don’t have a known relationship with riddles. - Even though he borrows the term ‘war machine’ from Deleuze and Guattari,

Negarestani’s war machine is not a nomadic force of dissidence opposite (or outside)

of the State. It is a tactical tool born from and devoured by the (Un)Life of War for

strategic advancement. Negarestani, accepts War as a radical outside, and not as

war-as-machine. He talks about how Assyrians develop Lamassus as new and

improved war machines to beat War (Cyclonopedia, 2008). - https://journals.ku.edu/jdtc/article/view/3559

Exhibition credit: Merve Ertufan, Kafakurcalayan, Depo, İstanbul, 2020-2021.

Photography credit: Ali Taptık, Onagöre.

For more information;

https://www.border-l-e-s-s.com/merveertufan

Merve Ertufan – Waiting on a Scratch – Depo İstanbul (depoistanbul.net)