Sense of Earth focuses on the word “terroir,” which refers to the combination of factors such as soil, microclimate, terrain structure, slope, altitude, and the myriad of geographical features that give wine its unique characteristics. The exhibition presents a structure that hears, senses, and attempts to understand all the elements that give the vineyard its soul. The century-old roots that emerged while establishing the vineyards, previously a sunflower field, prove that this land has long been a home to grapes. Rising from its ashes and once again becoming a home for grapes, the land now embraces creative interpretations with the intention of enriching the treasure it holds.

The Barbare Vineyards routed us to unearth the hidden stories and the forgotten values of geography. One first notices the mountains, sea, sunset, and fertile fields that change color throughout the year. However, after spending more time and paying closer attention, the dominant presence of humans makes itself apparent. This is a place that’s alive. The direction of the wind, horizon lines, naturally formed elevations, and the bios displaced by human oppression… Trying to remember the lives that once existed on this land, we sought to make sense of what emerges from beneath the soil when we dig and the new worlds built upon it.

Prepare to encounter an understanding that reshapes the boundaries of the land while interpreting the perspectives and colors offered by the landscape. This conception seeks to intertwine all that lie alongside the physical components of the soil that give life to the grapes; culture, myths, past, and present. As the biodiversity of the vineyards and their surroundings turns into textures, lines, and forms, we ask questions about the impact of agricultural activities on the land and the controversial aspects of the concept of ownership.

We have aimed to make the invisible visible, to track traces in nature, and to create and nurture a balancing force among the natural conditions within which the land functions. Although we feel that we have begun to hear the land, this is only the prelude. As we share this journey with you, we invite you to walk among the vineyards and seek answers to our questions together.

Lalin Mercan draws inspiration from the mythology of dogs frequently sacrificed by the Thracians, whose skeletons were also encountered in excavations. This story was reinforced by a dream the artist recently had. The roof imagined in the installation signifies the collapse of human civilization, while the god-dog standing atop it emerges as the ruler of a new one. This scene conveys the remnants of the civilization built by dogs and their myths. The constellations of Canis Minor and Canis Major, named by humans after dogs in spite of rejecting them from their own realm, are now claimed by the god-dog. Thus, the value they deserve is delivered to the stars by those who bear their names. The coins placed on the installation carry the symbol of a sip taken from the bowl of consciousness, which bestows natural power upon dogs. The ivy surrounding the dog heralds the collapse of one civilization and the birth of another.

When Eve walked among

the animals and named them—

nightingale, redshouldered hawk,

fiddler crab, fallow deer—

I wonder if she ever wanted

them to speak back, looked into

their wide wonderful eyes and

whispered, Name me, name me.1

1Ada Limón, A Name

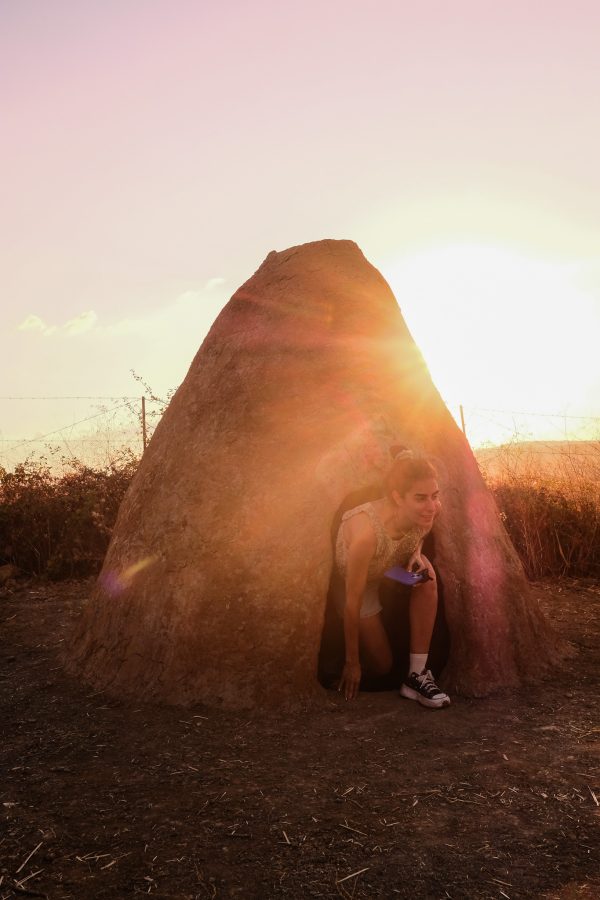

Dilan Bozer, Mother’s Womb, 2024,vEarth, reed, willow, 220x 220 x 250 cm

In this particular piece, Mother’s Womb , Dilan Bozer attempts to interpret her personal narrative through the lens of collective mythology. Drawing inspiration from the cultural heritage of tumulus structures in the region, she crafts her work from stone, soil, and clay. Though it appears as a mound from a distance, it represents the navel of the land. Tumulus structures are typically known as monumental burial sites, holding the body and objects that define an individual’s life. However, they also symbolize more than just the physical end of life; they embody a belief in the possibility of rebirth and the emergence of a new life form. They remind us that every individual’s journey begins in the mother’s womb and returns to the greater womb of the earth. Harvesting wild clay formed over thousands of years by the ancient seas and layers of sediment, the structure’s particles contain the region’s geological history. The artist conveys the cycles of life through the metaphor of the womb that shapes and defines life. By working directly with this temporal material, the artist finds a way to communicate with the accumulated memory of past and present civilizations and listen to the story of the land. Inviting viewers into the structure to share this experience, she borrows the landscape from the viewers’ sight and proposes perceiving the landscape through senses such as intuition, sound, smell, or touch, embedded within the womb of the earth.

Through the seesaw designed for Barbare Vineyards, Cengiz Tekin attempts to interpret nature’s balance through an unnatural situation. Since the object is stuck in the ground and cannot move up or down, it presents a structure that is disconnected from its purpose, unbalanced, and uncoordinated. It now resembles more a sculpture than a seesaw. The vibrant colors of the seesaw evoke the playfulness of a children’s park while also referencing the site-specific map the vineyard uses to differentiate grape varieties. Through the sculpture, the artist expresses the loss of natural balance by disrupting the function of a toy based on equilibrium.

For Barbare Vineyards, Nicholson incorporates sculpture into his practice for the first time. While the thickness and depth in his paintings approach three dimensions, the structures in the landscape merge in the artist’s mind and form an installation. He creates a world with familiar yet tenuous objects. The functions of parts oscillating between a piece of machinery, an inter-dimensionally invasive plant species, or a shrine are ambiguous. The capacities and limits of the local materials he uses (machinery parts, construction iron, thread and textiles) guide the artist as he realizes his works. During the production process, the inevitable communication he establishes with the Barbare landscape, the wild grasses moving with the wind, and large-seeded plants are unknowingly incorporated. The shapes, strings and patterns on the work render the sculpture more empathetic and accessible; on the other hand, these details are like parts of an unknown ritual. The artist’s aim is not to be overly dogmatic but to provide an entry point for people to feel a sense of connectivity and nostalgia for a universally shared experience, enticing them to engage with and question the world we live in and the structures we have put in place.

Serra Bilgincan, Reptila Culivatus, 2024, (Un)functional Sculpture, vest, helmet and assembling manual; Stainless steel, steel rope, polyester sling cloth tow rope, plaster, plastic, plastic tube, digital print, 160 x 280 cm

Just as aerating the soil is essential for cultivating ideal grapes—a factor that influences both production and the taste of wine—walking among the vines compacts the soil, hindering its ability to breathe. Based on this knowledge that she gathered from vineyard workers, the artist designed an object that tills the soil as one walks, to create a balancing force and turn harm into productivity. Functioning as an extension of the body, the design resembles a cyborg*. By synthesizing the current state of the agricultural revolution, mechanization, and standardized mass production methods with an ecological and cognitive framework, the artist offers an alternative proposition for the transition of creativity from muscle power to brainpower. Inspired by cultivators used in the vineyard, the artist considers walking with it attached to one’s back as an active gesture. When not in use by the artist, the design transforms into a contemporary object with an explanation resembling an IKEA instruction manual.

Dilşad Aladağ invites the viewers to the vineyards with accompanying sounds of bird species specific to this geography and a text read by the artist. The work is inspired by Aladağ’s encounter with the Land Law of 1858, which allowed the claiming of a 3 diameter land around a tree by grafting and cultivating them. As a result, the land evolves into vineyards, and with nurturing care, the trees yield remarkable fruit. In a sense, this gives hope to industrial agriculture, in the Anthropocene age. No matter how much man transforms the tree’s chemistry, trees somehow remember its wild state. This brings hope against industrial agriculture and the Anthropocene epoch. This shows that trees endure their original state despite human intervention representing resilience and the unyielding connection to its origins. The artist also interprets the law about the issue of scalability. As one listens to the sound recording and walks through the vineyards, they encounter textiles with some holes in different patterns, manifesting as imaginary seals at a 1:1000 scale model of the 3-meter diameter area referenced in the land law. These holes symbolize grafted tree saplings while the rest claim the property, she addresses concepts such as density, succession, singularity, uniformity, and randomness.

- Artists: : Dilşad Aladağ, Valentina Bacci, Serra Bilgincan, Dilan Bozer, Didem Erk, Berkay Kahvecioğlu, Milo Kester, Lalin Mercan, Rhian Harris Mussi, Sam Nicholson, Büşra Özdemir, Furkan Öztekin, Arthur Rabut, Eda Şarman, Cengiz Tekin, Murat Yıldız

- Exhibition credit: Courtsey of the artist and Barbare Studio, Sense of Earth, Barbare vineyards, 2024

- Photo credit: Fatih Yılmaz

- For more information; barbarestudio.com