THE UGLY DUCKLING

Silence. Darkness.

The unknown.

In a split second, energy is concentrated and erupts with a deafening force, scattering into stardust. In a weightless void, where even warmth falls outside of definition, millions of scorched dust particles try to extinguish their flames after the explosion. It burns so intensely that cooling down takes billions of years.

In one of these particles (or in countless unknown thousands)—a single cell moves quietly within cooling water, seen by no one. It has no witness, yet its knowledge is certain and ancient. This first movement expands from the pressure of its own nothingness. Water nourishes it; it, in turn, draws life from water. What a magnificent sea! Cells, fluids, a universe expanding through communication. It divides, multiplies, and reproduces. It becomes itself by separating from its counterpart. It resembles its ancestor but is not the same; it comes from it but does not belong to it. It belongs to water. As the water moves, the cell grows—or as the cell grows, the water ripples. Our first connection with the world begins here: in the body.

In a scene from the movie Red Desert (1964), a child asks his mother: “Mom, what’s one plus one?” The mother says, “Two.” The child drops two droplets of water onto a microscope slide. They merge; no longer two, but one. The mother is mistaken. “Our genomes are catalogs of instructions, filed to cope with every unexpected scenario from all sources in nature.”[1] Water is the most primordial cradle of this knowledge. The first state of existence in the womb, the life vibrating within a single cell, the evolutionary motion that began in the ancient oceans, or a shared origin formed by cosmic energy. 1+1=1 doesn’t question the singularity of origin, but rather brings us closer to the idea that things exist through interaction, fusion, and communication. Movement is the sign of energies, of birth, of encounters between molecules and cells. The question of belonging resonates not only in the light of time but also in its darkness—and in the perception of the body. The Nightbathers portrays a body searching for belonging in the depths, in the darkness of water. Were not the primordial waters dark too? Just like in the womb. We are in the darkness of life-water. This is why being in water at night feels more natural than during the day.

[1] Thomas, Lewis. The lives of a cell: Notes of a biology watcher. Penguin, 1978.

Images shaped by algorithms and generated through AI interactions give birth to Daughters (Phase II). Limbs, bodies, organic but undefined forms—despite technological censorship— evoke a cell, a chromosome, or an organism. Even when blurred due to the inappropriateness filters of modern devices, they continue to reference a chromosome, the smallest form of “life.”

That “life” might be a drop of water or the depiction of a cell—or perhaps a birthmark on a mother’s back that appears in the same place generation after generation. A hole, a Chimera. A bottomless black dot. If we were to fall into it, we might drift through a universe encoded with all the knowledge of genetic memory. The multiplying mother passes on more than just a bodily trace—she inherits ancestral knowledge. That “mark” carries the memory of identity. The transmission of mitochondria will be reinterpreted in the body of the daughter. What an extraordinary piece of knowledge. A small dot, a connection full of embodied meaning. An invisible umbilical cord.

Or the umbilical cord itself. Maman. “Home is both body and soul. It is the first world of human existence.”[1] This home is first inhabited by the mother as host. The mother is not only a biological entity but one’s first home, historically, mythologically, and semiotically. Like soil that nurtures a plant, she lifts life to the skies from her womb. The first place of existence is her; the first nourishment, her milk. Her body is the space of our earliest sense of belonging. Safety. Within that shell, one lives in a state least affected by external forces. Eventually, even that protective shell opens. Within it, the body exists with the mother; outside, it must be experienced alone.

This temple—the body—is not a singular subject but a network of relations. It exists not only as a vessel for belonging but also as a surface upon which belonging is redefined. The boundaries of the body are not only physical but also emotional and cultural. The sense of belonging sometimes emerges not from self-perception but through connections with other bodies, objects, identities, relationships, or geographies.

Every displaced individual turns their body into the space of their identity, culture, and memory. For it becomes their only home—or something else to which a home is attributed: an object, a movement, a moment. Nomad, always on the move, resembles a turtle carrying its home on its back. In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, belonging is third, and the inability to access it interrupts the next stage—the need for self-esteem and respect from others. This lack infiltrates all of a person’s relationships with the world. For a painter, it might be a suitcase never unpacked, always there, shifting, restless.

[1] Bachelard, Gaston, and M. Jolas. “The Poetics of Space. Gaston Bachelard.” (1958).

For someone else, it could be a quilt produced using traditional techniques. Its traditionality feels even warmer than the physical warmth it provides. The comfort, protection, and sense of safety it offers culminate in The War Heirloom II, Scorpion I. The scorpion figure embroidered on the quilt turns a protective object into a threat. Sleep—such an untouchable act—is disturbed by this image. The scorpion seeps into peace and asks, “Are we truly safe?” How much of what we consider comfort is truly ours? How much of it is from us? These questions extend not only to beds, belongings, or spaces, but also to the language, culture, and community we feel we belong to.

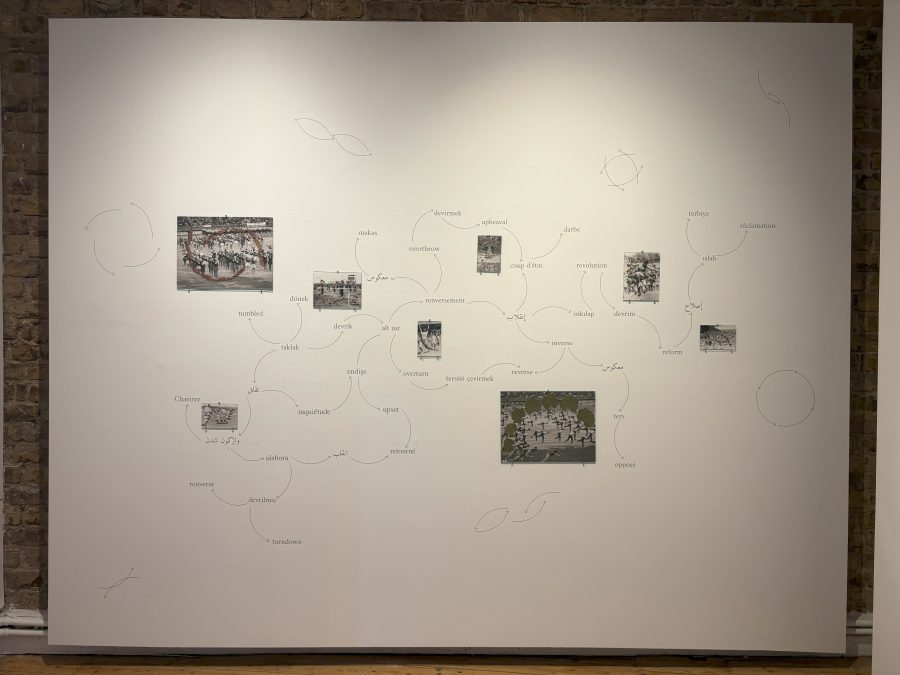

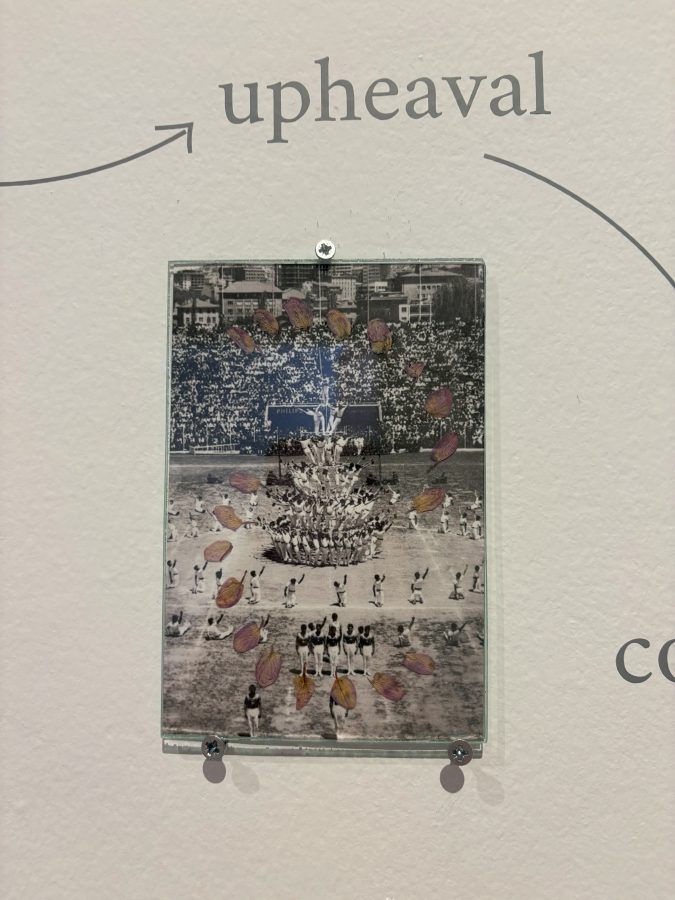

We may search for the roots of our identity in the story of a flower. Sometimes, beyond our bodies, we reappear in the flora of where we come from—in the form of a flower unique to its nature. Its story can suddenly become ours. In national celebrations, the body appears on stage as a political tool. Movements adorned with disciplined, military choreography translate the desires of power. The performance becomes a representation of obedience, order, and loyalty. Upon these familiar visuals, the Somersault Flower appears, its form aligning with the rhythm of bodily movements. It wanders through the uncertainty of what form of bodily discrimination one might face while escaping from bodily nationalism in foreign lands. It turns, rolls, or tumbles. And then the question arises: How many times do we have to tumble to adapt to these new lands?

Dilşad Aladağ, Kinetic etymology map – How many times do we have to tumble?, 2025, dried redbud collages on photo prints, various sizes

A lullaby from afar soothes the body. It is soft, inclusive, and gentle. It brings us closer to the feeling of belonging—to a mother’s embrace. These folkloric melodies, unique to each geography yet stirring the same emotions in all, carry one—no matter how far—back home, to childhood, or to cultural roots. Trans-lation creates a hybrid structure by blending the mythologies, tones, aesthetics, and languages of different cultures. It shows that belonging is not static, but dynamic. A constant effort of attunement—then another, and another. This points not only to a spatial quest but also to what one hears, remembers, and what one softens and calms within. As of a new culture and nation emerging, belonging to a lost civilization. This new body takes on the form of fantastical, androgynous, genderless beings free from conventional definitions. It transcends the ingrained perception of the body; it announces the autonomy of unrooted forms.

Understanding the bodily manifestation of belonging is shaped not only by physical but also mental layers. The bonds we form with home, city, culture, language, belief, or social groups shape everything from the body’s movements to breathing rhythms, stress levels and posture. So then—when one truly feels belonging—what form does the body take?

April, 2025

- Artists: Dilşad Aladağ, Zeynep Beler, Serra Bilgincan, Mustafa Boğa, Dilan Bozer, Yekateryna Grygorenko, Fırat İtmeç, Alix Marie

- Exhibition credit: Courtsey of the artist and Martch Art Project, Oriented body, Martch Art Project Istanbul, 2024

- For more information; https://martch.art/exhibitions/