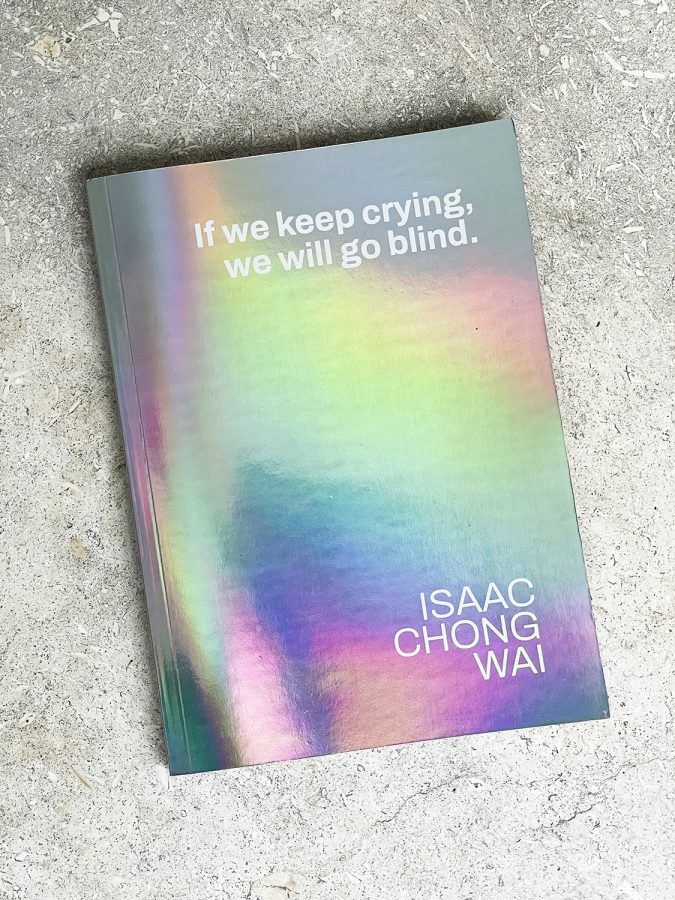

Isaac Chong Wai adopts a narrative that publicly re-evaluates notions concerning the entirety of society; such as power, violence, collectivity, leaderlessness, and mourning. Actively carrying out his artistic practice since 2011, Chong reinterprets certain events that took place in recent history in a contemporary vernacular. When I took a deeper look at his work prior to and during the exhibition, I noticed some common points that have gradually embedded themselves within his practice. Among these were fragility, emptiness, and subtle disruptions of systematics. Although this introduction concerns the exhibition If we keep crying, we will go blind. in particular, it might be helpful to keep in mind these qualities while reading the catalogue.

In his last solo exhibition Leaderless (2021, Istanbul) he envisioned a future without leaders by challenging us to construct a world in which centralism has lost its validity. In this exhibition, Chong proposes a leaderless moment once again, only this time focusing on funerals of state leaders that took place in public spaces, with an emphasis on the repressive atmosphere that remains despite their absence. He observes the body language and facial expressions of the mourners and examines the connection of the individual to the nation through the lens of personal emotions. In other words, he deals with the politics of death by pointing out how the act of mourning can be used as a means of propaganda over society, thus upholding an implicit political campaign. Revealing how authority permeates the public’s mourning and tears, Chong takes us to the brink of imagining a free society in which emotions can be freely expressed. Chong’s critical gaze is embodied in the exhibition by large-scale installations, silk-screened prints, a lightbox mirror, and a performative video.

Blindness is often defined by darkness; on the contrary, light is the fundamental component and most basic input of the sense of sight. The warning “if we keep crying, we will go blind.” points out how people are distanced from their own ideologies by a system in which the emotional expressions of society are controlled by the state. The notion of blindness in the title not only refers to the physical loss of sight but also recalls the potential of immersion into mental darkness.

Ed. 1/3 + 1 A.P.

The two installations in the heart of the exhibition, titled Crying Streetlights, were inspired by the street lamps in prominent squares in North Korea and China. Ordinarily meant to illuminate the squares and guide people in the dark, the lamps in Chong’s installations are presented as dysfunctional, hollow, unilluminating objects, signifying blindness. Engaging the gaps by partly covering them with chains, Chong places tears as an allegory on the street lamps and thus anthropomorphizes them as the silent witnesses of public mournings. As indirect depictions of the public spaces representative of a nation, the street lamps are ordinary actors on the stage of the control mechanism that creates an ironic sense of security over society. I think the notions of emptiness, absence and fragility in Chong’s works become remarkably relevant at this point. Chong conceptualizes absence by systematically filling it with different spectacles, objects that are fragile both materially and essentially. The mention of the other is embodied by the delicate but undeniable authenticity of these objects. His depictions of absence were once found in a cast glass tracing a wound inflicted through violence, now in a delicate chain adorning a neck. Absence and emptiness recall the presence and absence of the other.1 Every drop of a tear descending from the eyes of a people who have lost their leader is represented here with chains, each link of which is blank. These spaces emerge as black holes enabling one to see the past or the future, a forceful warning, recalling the other’s presence.

In the silkscreens dispersed throughout the walls of the exhibition, Chong addresses photographs of people crying in the aforementioned national funerals of state leaders. His interventions on the tears give them exaggerated visibility. The cable chain curtains that fall on the prints demarcate the fine line between inside and outside, personal and public; the interventions on the tears emphasize the vagueness between true sorrow and exaggerated expression. The physical features and functionalities refer to the conceptual dualities present in the exhibition: public-individual, strength-fragility, precious-ordinary, subtle-forceful.

Additionally, I think the most vital detail of the series is implicit in its title. Chong calls the series Crying People instead of ‘Mourning People’ and thereby questions the basis of mourning. Are tears shed because of love for one’s leader? Or is that mourning designed by a state whose public is obligated to obey it? Are the laments intended for the person or for the death of authority? The photographs don’t infer clearly whether the people are genuinely sad or performing an extravagant pretension. Another significant point in the title is Chong’s emphasis on counting, something also encountered in his previous works. In 2019, he painted prison fences in the Lines Series and titled the work through the numbering of each bar. This time, by counting the crying people in the images, I think he is somewhatembedding his criticism in these numbers. The numbers leave people indifferent to the actual subject. The individuals in such visuals were serviced to the whole world to be representative of the nation, without revealing any individual identity. Therefore, the people crying for the nation mattered to the state not for who they were but for their numbers. Such disregard and reductiveness also stand for the nation’s own choices; ‘the feelings of the state’2 to put it in Chong’s terms. This presence without identity thus becomes significant through Chong’s act of counting and asserts his defiance against the generification of individual existences.

The video Controllable / Uncontrollable Tears analyzes the emotional states of the mourning that prominently connect various pieces in the exhibition. When it comes to national mourning in a public space, the movements themselves no longer resemble traditional mourning rituals/habits but adapt the structure of state norms, distinguishing what is inherent in the public from the private. In a video showing faces without expressions, the performers can be observed crying with or without tears. Two analogous expressions oscillate between authenticity and pretense. The question is how –and to what degree– one can externally control the personal and bodily experience of one’s inner feelings. The chains used in the video –also dominant in the exhibition– are a significant part of the performance. They connect the performers to one another, and function as both limit and guide for their movements, which subsequently evokes the interactions of a society’s shared mourning.

The titular work, a lightbox with mirror, deliberately leaves the word ‘blind,’ which the sentence underscores, in the dark. Among the writers of the catalogue of his former solo show What Is The Future In The Past? And What Is The Past In The Future? (2019) held in Zilberman Berlin, Caroline Ha Thuc mentions the artist’s Missing Space (2019) series, writing, “Mirrors metaphorically belong to a timeless world.”3 We hear the echo of that sentence on the mirrored lightbox, turned towards the visitors who watch the scenes of mourning from the past, apparently to recommend connecting to the present and imagining the future.

The coherence that each object and content come together to form in this exhibition solidifies in this catalogue thanks to Kaya Genç’s History’s Fur Hat: tears as ideological props and Joowon Park’s Politics of Mourning. Genç draws upon humanity’s conservation of history and memory in his text narrated around the story of a fur hat and makes a subtle connection with Chong’s ways of representing absence, whereas Park makes a distinction between mourning and grief, pondering its roots in the Korean nation followed by transnational projections.

The artist’s futuristic narratives about the collective being and the body, along with his political discourse, unequivocally highlight the significance of solidarity. In the exhibition If we keep crying, we will go blind. as well as his previous ones, Chong convinces us that it might not be so difficult to embrace a pluralist and inclusive consensus instead of a single self-centered mind, horizontal and homogeneous structures instead of a vertical and heterogeneous order regarding rights and equality, and the open and free expression of emotions instead of covert and inexpressible concealment.

- Güngörmüş, N. E. (2021). Sanatçının Kendine Yolculuğu: Sanat ve Edebiyat Üzerine Psikanalitik Denemeler (1st ed.). Publication of Metis.

- Zilberman Gallery. (2022, June 1). Isaac Chong Wai — If we keep crying, we will go blind. [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/715953110

- Ha Thuc, C. (2019). What Is the Future in the Past? And What Is the Past in the Future?. Zilberman

Exhibition credit: Isaac Chong Wai ve Zilberman’ın izniyle, If we keep crying, we will go blind. , Zilberman, İstanbul, 2022

Photo credit: Kayhan Kaygusuz

For more information;

https://www.zilbermangallery.com/if-we-keep-the-crying-we-will-go-blind-tr-e313.html

This introducion was published as an hardcopy on June, 2022 for in the exhibition catalogue by Zilberman.