In the exhibition Fake Mustache, Doğu Özgün explores one’s tendency towards the hierarchical structure and evaluates it through the lens of those in power and those who obey. The exhibition delves into the impulse of human obedience to authority or the dilemma of becoming the authority while resisting it, compelling us to break free from definitions and contemplate the gray areas. He addresses the psychological and individual aspects of an order that offers only two options to be a hunter or prey while exploring the behavioral symptoms that are reechoing in the society.

The artworks presented in the exhibition drag one into an uncanniness that is sensed but not fully comprehended through Özgün’s imagery, emerging in his canvases iteratively and creating its mythology by taking on representations of the objects to the beyond. Likewise it is subjected in the short story by Borges, The Mirror and the Mask; Özgün brings forth the dichotomy of the human beings’ passion towards the truth and will to show their authenticity openly with its tendency of disguising themselves with a variety of masks in front of society.

The exhibition focuses on personal stories, the conservative nature of the family resisting change according to the social norms, and the stance against the human mind to this notion. While influencing the function of the value mechanisms, this canon also conceives a society in which individuals are detached from their true identities, are focused on conforming to the perception of success, and are constantly self—questioning, criticizing, vilifying, raging, and punishing—. Through the exhibition, the artist expresses the fear associated with the concept of change and the tendency to adhere to established teachings, urging us to consider the internal and external reflections that may occur when stepping out of our comfort zone and asks: Can one survive by casting themselves outside the system and transforming? For an individual, initial experience with the cosmos begins with the safe and blessed bosom of the mother. In the work of Ninniler, Özgün points out the destructive side of the notion of family – motherhood that puts so much effort to the best of their potential ability. He emphasizes the circumstances caused by parents with their protective attitude towards their little ones who are unaware of the hardship of life thus, are frightened to get out of their shells. Along with the unreal subjects appearing on the canvas, the curtain detail encircling the frame is striking. This image is used frequently in David Lynch movies. Lynch creates an indirect verge where reality and dreams merge with the help of the curtain metaphor to the extent of its features related to sacredness and exposure.[1] Özgün applies such kind of verges each time differently in his works titled Exit, Ozmofobia, Öfke, and İntikam. These appear, sometimes as a door, only seen to the careful eyes, masterfully placed at the corner of an intricate room, other times, as a backside of a canvas that is generally unshown to the viewer and exposed by bringing it to the obverse side of the canvas. Thereby, the idea of a threshold is reinforced both in the image and intellectually. The artist applies the same ideology by pealing the picture like a shell and extracting new paintings from the same canvas. Thus, the inner side becomes the outer and vice versa. While this play in between the canvases reiterates, the dilemma of the mask and the mirror strengthens. At this point, the urge to delve deep, exposing, refining, and mending evokes and becomes prominent in Özgün’s works.

Amidst all the confrontations and getaways, the necessity to live within a community according to its standards and the need to feel a sense of belonging all point to the search for a new comfort zone. In the artwork Rootless, we discover a plant firmly rooted inside a car through an unordinary composition. The impossibility of a voluntary location change for a plant is shattering in this painting. The plant takes root in the steering wheel of a mobile object like a car, disrupting conventions and bringing contradictions onto the canvas.

Philosopher and culture critic Byung-Chul Han, who introduced the concept of the hell of sameness, suggests that in current world dynamics where everyone tries to resemble each other, the only way to escape this hell is to establish a connection with what is called the other. [1] The tendency to homogenize society and to find the “other” as wrong, impertinent, and unpleasant is not only causing problems related to belonging but also similarly affecting one’s self-confidence, standards of success, and value mechanisms in society.

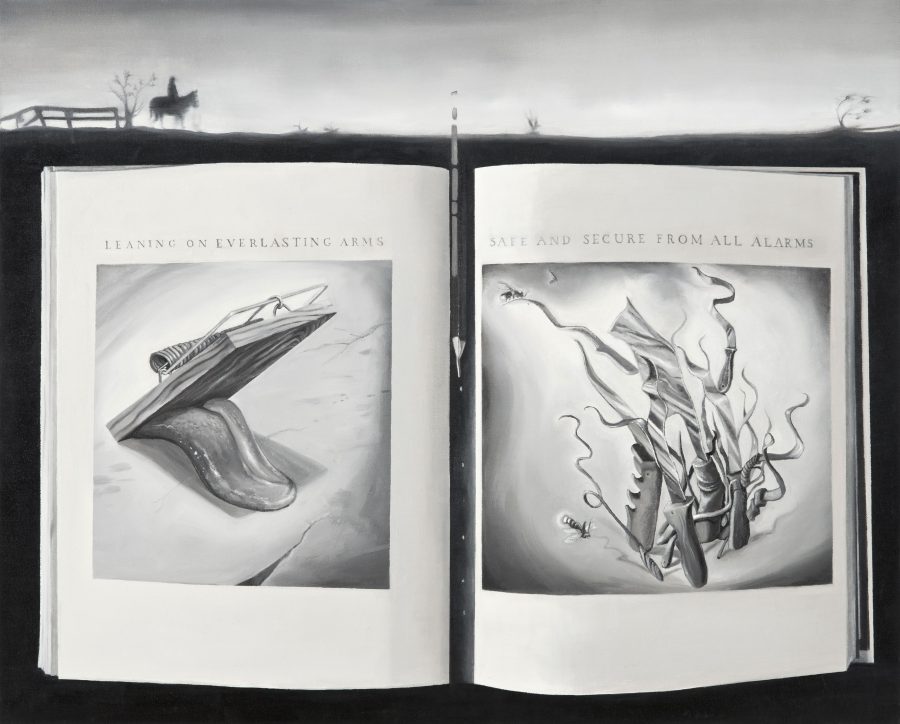

Within this system, where we are constantly obliged to turn the mirror towards ourselves, Müdara presents a dark visual of a character confronting their fears. The canvas, composed of different layers, portrays a childhood through scribbles drawn on notes left by an adult who used to follow the melodies of the piano. The scribbles include a bee and a child’s drawing behind the bars. In the third and final layer of the painting, fragments that resemble nightmares and fears pierce through the musical notepad, turning them more realistic and bodily than all the narratives in the painting. In other words, the character’s fears, which have been engraved in the musical notes of composition since their childhood and dominate their life, are realized. On the other side, a tongue turns into a trap, and knives mimic dancing flames in the painting Leaning Leaning, emphasizing that danger is not a sharp knife or a swift trap but rather the subject matter that pretends. The artist gets inspiration from the movie The Night of the Hunter for this piece and incorporates an ironic quote; “To lean on these trusting arms is better and safer than all the warnings.”

The connection of fear, trust, and defense mechanisms seep into emotions’ from childhood and range to every period of life in various ways, ultimately making society selfish and devoid of empathy. The constant desire for power and the effort to gain permanent supremacy results in psychological warfare between rivals who wear different masks. Is this persistent war truly inherent in human nature? Revolving around this question, the artist welcomes the viewer with a mustache -giving its name to the exhibition- painting placed within a nametag. Fake Mustache relates to the childish wish to own everything with the proud gaze of the bosses dictating and oppressing masculine language. In fact, the figure is now starting to resemble a childish adult wearing a mustache that generally represents the language of masculinity, authority, and supposed wisdom. The artificiality is not limited to his fake scrub but to the strange value system taught to him and practiced by him. A sculpture called Sabotage goes well with the abovementioned childish forgery that is a pen self-erasing and sabotaging itself. The pen is the most commonly used object by the patron who stays at the helm of the stagnant system and exposes the inefficiency of each signature it makes. The paradoxical repetition of writing and erasing action sends us back to the abyss of the hell of sameness.

*Borges, J. L., Di Giovanni, N. T., & Reid, A. (1977). The book of sand. New York: Dutton. [1]Fisher, M. (2017). The weird and the eerie. Watkins Media Limited. [2] Han, B. C. (2017). The agony of eros (Vol. 1). MIT Press.

Exhibition credit: Courtesy of Doğu Özgün and x-ist, Fake Mustache, x-ist, Istanbul 2023 Banner: Exit,2022, oil on canvas, 54 x 72 cm Photo credit: Mesut Güvenli For more information; https://artxist.com/Exhibitions/Fake-Mustache/230